New MERICS index: how internationally integrated is China's economy?

Key findings

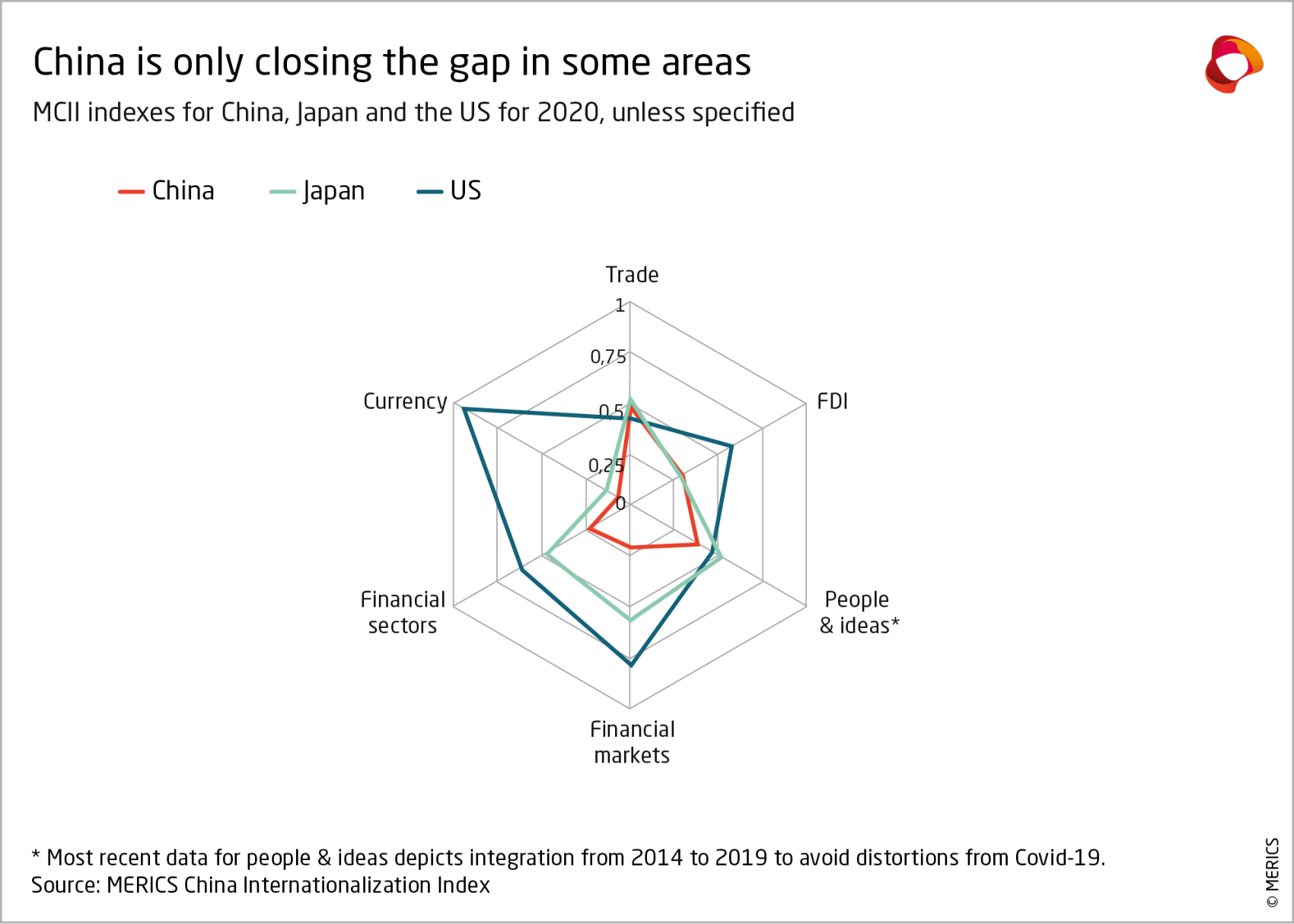

- The MERICS China Internationalization Index (MCII) shows that the Chinese economy remains substantially less integrated into the world economy than the US and even Japan, despite years of growing international exchanges. China’s dominance in industrial exports can lead to an overestimation of its global role. Its economy remains more isolated than its manufacturing prowess suggests.

- These disparities in Chinese global economic integration are the result of a selective and sequenced approach by Beijing. Contrary to the largely principles-based approach of more advanced economies, China has shown a more transactional approach, advancing economic integration only if this promised gains elsewhere: the MCII reveals that opening up was aimed at securing commodities, investment and talent for China.

- China’s recent emphasis on national security points to a “slowbalization” of its economy, making it unlikely the country will become as globally integrated as the US any time soon. Xi has not rolled back China’s opening-up policy, but its drivers have in recent years been exclusively formal changes, especially in the financial sector. In terms of actual cross-border exchanges, China’s international integration stalled around 2016. It appears that the more challenging political environment in China and globally has discouraged actors.

China is the world’s factory – but less integrated into the global economy than the US and Japan

The new MERICS China Internationalization Index (MCII) shows that China is still significantly less integrated into the global economy than the US and even Japan. Despite two decades of fast increasing economic exchanges with other countries, China's MCII Internationalization score of 0.3 in 2020 was only half the US score of 0.6 and a third lower than Japan's score of 0.4. This seemingly startling difference reflects the fact that China's integration into the global economy has been largely driven by real economic activity – tangible actions such as trade, foreign direct investment, the movement of labor, and the exchange of ideas – and less so by the financial economy and its vast but intangible capital markets and related services.

The MCII shows how much more integrated China's real economy is with the global economy than its financial economy. This discrepancy between China's strength in the "visible" economy and its relative weakness in the "invisible" one suggests why China's integration into the world economy is often a contentious issue.

Perceptions of China's global economic status vary widely, ranging from predictions of eventual dominance to assertions of inevitable decline – both within China and abroad. The unprecedented speed of China's rise from a developing economy to a global powerhouse and the complexity of defining and measuring economic integration only complicate balanced analysis further.

To contribute to a more objective understanding of China's global economic integration, MERICS has developed a data-driven tool to assess the internationalization of the Chinese economy since 2000 (the latest year is currently 2020, see the annex for more methodological details).

The MERICS China Internationalization Index measures the extent and modalities of China's economic integration with the rest of the world and compares it with that of two other prominent international actors, the United States and Japan. (The European Union had to be excluded due to data availability problems, and EU member states were excluded given the difficulty of comparing intra-EU economic exchanges to external ones.)

MERICS is launching the MCII as China is recalibrating its engagement with the world, which will have profound implications for globalization. Xi Jinping’s emphasis on national security over economic growth has blurred the objectives Beijing for at least two decades assigned to its international economic exchanges. The country’s “opening up” no longer aims to attract foreign resources to spur economic development and instead refers to China reaching out into the world to secure desperately needed technologies and supply chains for Chinese industry.

The relationship between China and the United States remains tense. The mutual co-existence that over the past four decades helped China integrate with the globalization is crumbling. The economic frictions between the two countries have grown from gripes about balance of trade to higher tariffs in imports and controls on the export of select essential technologies. China's readiness to use economic coercion against other countries and its support for Moscow during Russia’s war on Ukraine have strained relationships with most advanced economies. Many of those countries are trying to „de-risk“ their dealings with China, questioning the wisdom of deeper economic integration as the way forward and even pushing for diversification in critical areas.

Any change in the way the world interacts with an economy as large as China’s will be profound. The scale of China's international economic activity has become immense, meaning that any changes will have significant impact on global goods and financial markets. China’s global trade activity in goods hit $5.9 trillion USD in 2023, 20 percent of the world total, and in the same year it secured a stock of $5,5 trillion in foreign direct investment (FDI), roughly 10 percent of global FDI.

Beijing's bilateral official lending, almost non-existent two decades ago, now exceeds that of the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank put together. In addition, China's education and tourism footprint is vast, with nearly one million students studying abroad and 155 million annual outbound tourist trips before the Covid-19 outbreak in 2020.

The MCII provides a baseline for assessments of the evolution and future direction of globalization in the light of China’s economic shifts. Made up of more than seventy components, the MCII encompasses a dozen subindexes that capture the various economic channels through which an economy integrates with the rest of the world. To provide greater information, each (sub-)index has four sub-dimensions capturing (1) the importance of the world for China, or the China perspective, (2) the importance of China for the world, or the world perspective, (3) the de facto value and (4) its de jure counterpart.

A data-driven analysis of the international interlinkages of the Chinese economy allows a more sober assessment of its role in the world economy. Aggregating such a complex phenomenon like economic integration into a single metric has its limitations. But the depiction of relative strengths and weaknesses through the main index and its subindexes does shine a light on important aspects of our complicated and highly connected world. Despite China’s undeniable strengths in many dimensions, they show that the Chinese economy remains nowhere near as important to the global economy as that of the US.

The days in which Beijing could pick an economic dimension and successfully drive its integration with the global economy are over – this applies to both internal and more security-focused international exchanges mentioned above. This analysis reviews China’s integration with the world economy over the last two decades. Despite recent attempts to take countermeasures, the Chinese financial system remains much more isolated than the real economy. To understand why this is so, it is useful to divide China’s economic integration since 2000 into three distinct periods, which are discussed in detail in the next section.

Changing drivers mean China has seen three stages of global economic integration

2000 to 2008 – export-driven integration that pushed China’s trade surplus higher

In the first decade of the 21st century, China’s integration into the global economy was primarily driven by trade. “Opening-up and reform” throughout the 1990s and China’s accession to the World Trade organization in 2001 had set the points for China to become the global manufacturing hub. Exports of Chinese manufactured goods, be it in the form of finished goods of inputs for other products, boomed in line with strong demand from consumers in advanced economies. The country’s exports as a share of gross domestic product (GDP) reached an all-time high of 37 percent in 2006, before trending back to 18 percent in 2020. Since China's imports of foreign finished goods and manufacturing inputs did not experience the same growth momentum, the value of China's trade surplus reached new heights every year until 2008.

This phase of integration also saw an uptick in cross-border flows of people and ideas, albeit from a very low base, as China’s need to attract foreign expertise and technology grew. Opening up to a substantial influx of foreign brands and expertise, China began paying hefty sums for the domestic use of foreign intellectual property – as much as 2.4 percent of GDP in 2006. Chinese students ventured abroad to study in the West, accounting for 11 percent of the worldwide international student population in 2012, up from a meager 2 percent in 2000. International students studying in China also became more common.

Foreign investment in China had accounted for a substantial 10 percent of total capital accumulation in the 1990s. But it became less important after 2000 as Chinese savings and capital accumulation soared. The more limited expansion of market access after WTO accession in 2001 did not help. Despite Beijing’s efforts to promote international investment by Chinese companies through its “Going Global” strategy initiated in 1999, Chinese outward FDI only began to pick up significantly in 2012. On the financial front, the Asian financial crisis of the late 1990s confirmed the Beijing leadership’s distrust of cross-border financial flows.

2008 to 2014 – China’s first steps towards integrating its financial economy

Towards the end of the first decade of the new millennium, the global integration of China’s real economy slowed, and new drivers of integration emerged, particularly in the financial economy. Financial integration remained comparatively modest as Beijing maintained stringent controls on cross-border financial flows and the exchange rate of the yuan. But even this cautious opening kept the internationalization of the Chinese economy on a steady path through the difficulties of the global financial crisis of 2007 – 2008 and the subsequent slow recovery of many of the major economies in the rest of the world (see exhibit 3).

China's real economy continued to integrate at a slower pace as trade integration stalled. Sluggish international demand depressed Chinese exports, while China's post-2008 stimulus package only boosted imports of raw materials relative to Chinese GDP, as it focused on inward-looking sectors such as construction and infrastructure. In addition, an increasing number of foreign companies built capacity in China to serve the domestic market, reducing the need for imports.

The stellar growth of the Chinese economy relative to others during this period made possible two seemingly contradictory facts: the Chinese economy became more important to the rest of the world, while the economy of the rest of the world became less important from a Chinese perspective.

China in this period began to emerge as a significant provider of FDI. The country’s remarkable demand for raw materials to fuel its post-financial crisis infrastructure and real-estate boom encouraged Beijing to allow Chinese companies to invest in extractive and logistics industries around the world. In addition, cross-border student continued to soar. Chinese students seeking foreign academic qualifications by 2013 accounted for 11 percent of international students in the rest of the world. The number of foreign students in China almost doubled in this period, with 400,000 foreigners attending mainland universities in 2015.

But as overall trade perspectives became gloomier, Beijing turned to finance to keep funds flowing into the country. It enabled more sectors of the economy to tap foreign financial markets for debt and equity: Chinese developers issued bonds in Hong Kong, while many financial institutions followed the large state-owned banks in going public on the Hong Kong Stock Exchange. Balance-of-payments data shows that the foreign debt securities holdings of Chinese companies rocketed from 17 to 231 billion of USD in less than a decade. Chinese start-ups looked to US stock markets for fresh capital, almost tripling the foreign liabilities of Chinese entities in the form of equity securities to USD 617 billion. At the same time, foreign investors were given broader access to mainland financial markets, with the quota of Beijing’s main “Qualified Domestic Institutional Investor” program quadrupling to USD 40 billion by 2013.

International use of the CNY grew with China’s trading power and because of Beijing’s ambitions to challenge the USD’s centrality in the global monetary system. Over the period, yuan-denominated deposits held overseas rose from a negligeable amount to CNY 1.6 trillion. The internationalization of China’s currency was also boosted by investors betting on its continued appreciation against the dollar – after all the yuan had hardly experienced any depreciation against the USD between 2005 and 2013. Indeed, the yuan continued to do so until 2015.

2014 to 2020 – Xi widens the gap between formal and practical economic integration

Xi Jinping has continued the general trend of integrating China into the global economy – although his ambitions to create a more internationally powerful China have dramatically shifted the drivers. First, the period saw the emergence of a disconnect between the many formal steps towards economic opening enshrined in law (de jure integration) and the much more limited number of practical steps towards effective integration in practice (de facto integration).

Excluding all de jure openings, the Chinese economy has not become any more integrated since 2016 (see exhibit 4): greater de jure openness in many service sectors and efforts to lower tariffs have not led to a de facto increase in imports, while de jure efforts to ease restrictions on foreign players in many sectors have not led to a significant increase in FDI.

Second, Xi has made China’s financial economy a much bigger driver of overall global economic integration – and not even the domestic financial-market turmoil of 2015 and 2016 seems to have affected this. Foreign banks, insurers and asset managers saw a slow but sustained reduction in formal barriers. The integration of financial markets was driven by the development of new stock and bond “connects” between the mainland and Hong Kong, which from 2014 drew in dozens of billions of USD from foreign investors.

The BRI allowed the Chinese banks to aggressively lend abroad, resulting in more than USD 400 billion in net external lending to favored developing countries in less than a decade. Those moves to open up mainland China's financial sector led to a doubling of the financial integration sub-index between 2017 and 2020.

At the same time, an impressive increase in the de jure global integration of the Chinese financial sector has contributed to a growing presence of foreign financial institutions. Nonetheless, the renewed financial opening took place in an environment full of state-backed institutions that ultimately represent Beijing’s interests.

Key impediments to meaningful global financial integration remain untouched, including stringent capital controls on cross-border capital flows and the willingness of authorities to intervene directly and intensively in the sector when they feel the need. Coupled with Xi’s vision of an assertive China and the country’s growing distrust of “the West”, these factors will not help build confidence among foreign financial institutions for long-term investment.

China's global economic integration from 2000 to 2020 suggests three paths into the future

China is moving from globalization to “slowbalization” and will not match the US any time soon

Xi's goal of transforming China into an economically self-sufficient high-tech global superpower, and the G7-led “de-risking” response, mean that the global economic and geopolitical environment is now more challenging than at any time in the past quarter century. As a result, China's integration into the global economy is likely to continue at the slower pace established in the last few years.

The country’s rapid integration into the global economy from 2000 to roughly 2015 occurred despite significant constraints on China’s legal and administrative capacities – growth prospects and the political support of advanced economies allowed market forces to overcome ideological and political hurdles. Under Xi, these trends appear to have reversed, with ideology and politics now trumping economic considerations.1 China’s opening continues in an environment of slower growth and greater opacity. Beijing is still aiming for global economic integration, but with more conditions, even greater safeguards and enhanced powers to monitor and control the goods and capital flows of the real and financial economies.2

The widening gap between greater de jure economic opening and de facto economic integration reflects the dwindling appetite of foreign companies to do business with China. The G-7-led mantra of “de-risking” economic relations with China will only reinforce China’s shift from sometimes breathtakingly rapid globalization to “slowbalization”. Geopolitics has increased legal and reputational uncertainties for companies doing business with China.

The outflow of foreign capital from China after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine shows that international investors have recalibrated the risks of putting their money on the mainland. This has dimmed the prospects for financial integration, the area in which there perhaps is most further integration potential.

Recent developments hence suggest that over the next few decades China will not match the degree to which the US is currently integrated into the global economy. Extrapolating China’s past integration suggests that it could once have done so over the next twenty-five years. But in today’s more challenging geopolitical and economic context, China’s economic integration will slow, thwarting any ambition in Beijing of matching US levels of economic internationalization any time soon. It’s possible that China will not even match the economic integration of the Japanese economy in the foreseeable future.

Beijing has fared well with selective integration and will carry on relying on only a few drivers

Another feature of the China’s integration into the global economy is its heavy reliance on a few drivers – essentially trade and movement of people and ideas – stretching back as far as 2000. The US and Japan do also display impressive performances in some categories (see Exhibit 5). However, those unbalances have been much less pronounced relative to the area of relative weakness in their international integrations.

China’s de facto financial sectors’ and financial markets’ integrations score below the 0.1, as do some more granular dimensions such as the domestic perspectives on outward FDI or industrial imports. On the contrary, no tier-3 sub-MCII for the Japan and US score below 0.2, but for the Japanese currency.

Beijing’s reliance on only a few integration drivers reflects its political agenda. In the economically liberal and favorable international environment of the past two decades, China’s leadership chose to harness foreign FDI and demand to fast-track industrial development. At the same time, its ideological and practical desire to have the Chinese Communist Party steer and monitor the economy made it resist the liberalization of asset flows and price controls in the financial system.

Washington’s increased focus on global financial interconnections as an area in which to exercise international sanctions will surely only bolster Beijing’s reluctance. Similarly, the Chinese leadership’s industrial preference to favor domestic industry over both domestic consumers and foreign companies led to a limited influx of industrial inputs and final products.

Beijing is pursuing national security-driven, techno-industrial development. Given a less accommodating international environment, this will surely further unbalance China’s global economic integration.3

Beijing and Washington’s increasing focus on economic security will compartmentalize globalization

The US and the Chinese economies display inverse strengths and weaknesses. China is more dominant in the global trade than the US. Its commodity imports and industrial goods exports both score around 0.7 out of 1.0 in their respective MCII index components, making it hard to imagine the country ceding this influence in the short- or medium-term. At the same time, China is weak when it comes to the global integration of its financial economy – a field in which the US’s MCII index components hover just below 1.

In addition, the US and China are beginning to limit bilateral engagement in a growing number of critical sectors. With supply constrained in certain fields, both will have to find other countries that can act as substitute suppliers. The US will likely have to do this for industrial goods and China in financial intermediation, advanced technologies and financial assets to invest in. Barring any global conflict, the leadership of the US and China in different areas of global economic integration will lead to an incremental re-organization of globalization.

Concretely, third countries could position themselves as intermediaries of bilateral exchanges, based on needs and capacities. Some early evidence of a more fragmented globalization is already visible in fields that have suffered from tensions between China and the US. Since 2018, the two countries’ worsening trade dispute has, for example, seen Southeast Asia and Mexico import more from China and export more to the US as regional value chains have shifted. In research cooperation, a drop in bilateral cooperation on artificial intelligence has been partially offset by more engagement with other regions, especially Europe.4

This slow but steady compartmentalization of globalization is likely to accelerate. The two superpowers look set to redouble their strategic competition while being unable to offer a comprehensive package for third countries to fully align with them. Europe has already gone through this unsettling experience, aligning with the US on financial sanctions, while continuing to rely heavily on Chinese manufacturing imports.

- Endnotes

1 | Jacob Gunter, Max Zenglein (2023). The party knows best: Aligning economic actors with China's strategic goals. MERICS.

2 | Alexander Brown, Jacob Gunter, Max Zenglein (2021). Course correction: China’s shifting approach to economic globalization. MERICS

3 | Katja Drinhausen, Helena Legarda (2022). "Comprehensive National Security" unleashed: How Xi's approach shapes China's policies at home and abroad. MERICS

4 | Arcesati R., Kai von Carnap, W. Chang and A. Hmaidi, “AI entanglements: Balancing risks and rewards of European-Chinese collaboration”, November 2023, MERICS https://merics.org/en/report/ai-entanglements-balancing-risks-and-rewards-european-chinese-collaboration#msdynttrid=e_VxBfq7jnoDakS5OMGY21uyyuDDakMM949rRZ1VfCc

Annex I: The components of the MERICS China Internationalization Index (MCII)

The MERICS China Internationalization Index (MCII) shows how China’s economic integration with the rest of the world has evolved since 2000. The Cambridge Dictionary calls economic integration “a process in which the economies of different countries become more connected.” In this spirit, the MCII measures economic integration relative to the domestic economy of the country in question and the rest of the world. This prevents the MCII from becoming simply a measure of the size of an economy.

For most of the economic activities it covers, the MCII depicts a measure of that activity both as a proportion of that activity in the rest of the world and relative to the size of the domestic economy of the county in question. For example, total imports of a particular good are expressed as a share of total imports of the same good across the rest of the world and as a share of the importer’s GDP. In the case of a rapidly growing economy such as China’s, declines in economic integration can be caused by the dynamic growth of the domestic economy as much as by an increase in international exchanges.

To contextualize China’s integration with the world economy, MERICS charted the economic integration of other countries.

Components and computations

To reflect the complexity of economic activity, the MCII on tier one is composed of two tier two subindexes, one for the real economy, the other for the financial economy. Each of these is composed of three tier three component indexes covering between five and eighteen fields of economic activity, which are based on subindexes (cf. Annex II) on tier four. The second-tier subindexes are weighted to reflect their relative importance in the economic internationalization of an economy.

Each tier four component index is normalized from 0 for the absence of any integration to 1 for total integration into the world economy. Maximum integration is based on the theoretical maximums of several variables tracking different economic activities, as listed in detail in Annex II (below).

The tier two sub-indexes are weighted to reflect the traditional prevalence of the real economy (60 percent weighting) over the financial economy (40 percent). The former covers the economic activity of producing and trading tangible goods and services, including directs input used in production, the latter the exchange of financial products, such as money in return for shares, or credit for cash.

1. The real economy

The real economy is subdivided into the trade of goods and services (50 percent), foreign direct investments (25 percent), and the flow of people and ideas (25 percent).

1.1 Trade

Trade in goods and services is further subdivided into the trade in commodities (20 percent), the trade in manufactured goods (40 percent), the trade in services (20 percent), as well as the complexity of the products traded to give an idea of the economic quality of the exchanges (20 percent). Indicators of de jure trade openness in goods and services are included in dedicated subindexes, with the level of tariffs for the former and the degree of openness to foreign players in the domestic services market.

Trade in commodities is depicted by exchanges of oil, coal and iron ore, two energy-related commodities, and one commodity used in construction and industry. Two variables describe each one: import volumes as a share of domestic consumption and as a share of other countries’ imports.

For the trade in goods, imports and exports of finished products and intermediate goods are taken into account. Each series is then benchmarked against the country’s GDP and against imports or exports in the rest of the world. For the de jure dimension, a simple average of tariffs at the HS6 level is used.

Trade in services is represented by two variables – total trade as a share of total world trade in services or as a share of the GDP of the country in question. An additional variable depicts the average share of the country in world trade in services in the 11 sectors as defined in the official nomenclature of the balance of payments system (albeit without intellectual property, as described below).

Three variables capture the complexity of traded products: the share of domestic value added in exports of information and communications technology (ITC); the share of value added in exports of ICT from OECD countries that actually originates in the country concerned; a trade complexity index.

1.2 Foreign Direct Investment (FDI)

FDI integration is depicted by both FDI stocks and flows: the country’s stock of outward FDI as a share of the rest of the world's total FDI; the country’s stock of inward FDI as a share of the rest-of-the-worlds total; the country’s inward and outward FDI as a share of both the country’s and the world’s capital formation. The de jure integration indicator is the country's OECD FDI Regulatory Restrictiveness Index.

1.3 People and ideas

The global integration of the population is depicted by two variables for cross-border flows of people, four for flows of students, and one for the de jure openness. The exchange of intellectual property (IP) is captured by two variables: the country’s imports of IP services as a share of its domestic GDP and the country’s exports of such services as a share of such exports by the rest of the world.

Easily accessible international air travel figures are used to show the integration of passenger flows. They depict the number of international air passengers from the country under consideration as a share of domestic air passengers and as a share of the total number of international air passengers worldwide.

The four variables for cross-border flows of students combine the number of students from the country in question studying abroad as well as the number of international students in that country. These are compared with the total number of students in the country and the number of international students worldwide . De jure openness to flows of people and information is depicted by variables from an index compiled by the Swiss Economic Institute (KOF) at the Federal Institute of Technology Zurich.

2. The financial economy

The financial economy is composed of measures of the country's financial markets (50 percent), its financial services sector (30), and its currency (20 percent).

2.1 The financial markets

Two variables each for bonds, equities and loans (or “other investments” in official parlance) show the international integration in each of these financial products based on the balance of payments categories of the country in question. One variable shows the stock of investment in the country as a share of the domestic market. The other shows the share of external investment as a share of the G7 stock of external investments, as world data are not available. Two other variables show the de jure openness of financial markets and the cross-border flows of portfolio investment as simple averages.

2.2 Financial services sectors

The sub-index depicting the financial sector comprises three sets of five variables, covering banking, insurance and other financial services (primarily wealth management). For each of these segments, two variables capture the foreign presence in the domestic market, one relative to the total assets of the rest of the G20 and the other relative to the domestic market. Two other variables capture the footprint of domestic companies abroad, one relative to the G20 markets and the other relative to the domestic market. Each set has a variable to capture de jure openness, as provided by the OECD.

For the banking sector, the total assets of foreign-funded banks in the country are shown as a proportion of the total value of the domestic banking assets. The foreign assets of domestic banks are compared with the size of the total banking sector in other G20 member countries.

Data limitations mean that the presence of foreign companies in the Chinese insurance market is expressed as the share of foreign-funded insurance profits in total insurance profits in China. The foreign presence of Chinese insurance companies is assumed to be zero, as Chinese insurers face severe restrictions on doing business abroad. The domestic footprint of foreign players in other countries is derived from the share of domestic insurance operations of domestically owned institutions. The foreign footprint of domestic players from countries other than China is estimated on the basis of the value of their exports of insurance services as reported in their balance of payments statistics.

For other parts of the financial sector, the variables are based on wealth and asset management activities. The share of wealth management products offered by foreign-invested institutions is used as a proxy for foreign presence in the domestic market in question. As Chinese financial institutions also face severe restrictions on engaging in wealth or asset management activities abroad, these variables are set at zero. For others, dedicated OECD statistics for balance of payments are used. The domestic market is calibrated to the value of the total assets of different financial institutions.

2.3 Currency

Currency integration is depicted by fewer variables because it has fewer dimensions than financial markets or financial services. In addition, currencies do not lend themselves to the distinction between a world and a country perspective. This is due to the international nature of the foreign exchange (FX) market, which makes the distinction between domestic and offshore currency markets redundant. The subcategories used are payments, the FX market, FX reserves, and foreign holdings of the currency.

Annex II: The variables underlying the MERICS China Internationalization Index (MCII)

This "MERICS Report" was made possible with support from the “Dealing with a Resurgent China” (DWARC) project, which has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon Europe research and innovation programme under grant agreement number 101061700.

Views and opinions expressed are however those of the author(s) only and do not necessarily reflect those of the European Union. Neither the European Union nor the granting authority can be held responsible for them.